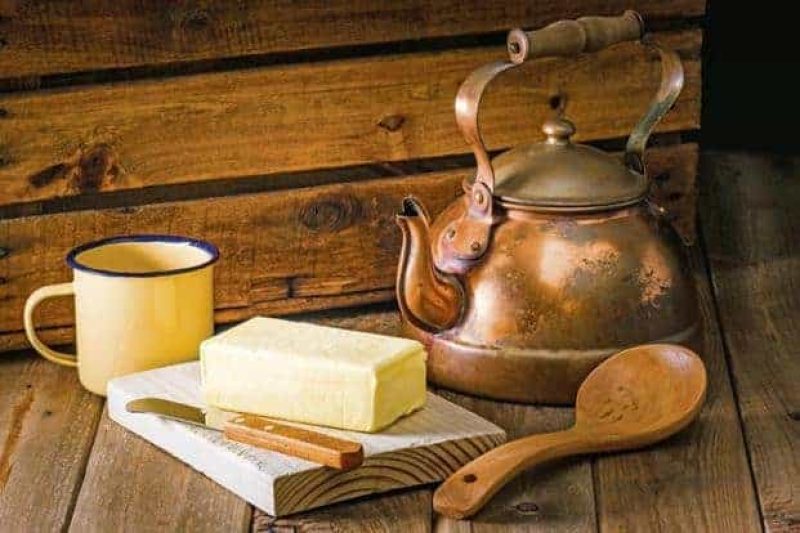

Conscious and Curious Chefs are Discovering the Virtues of Butter and ‘Ghee’ Anew

It wasn’t without serious misgivings that I stirred in a blob of butter into my cup of dark muddy coffee, watched it rise up in a fast-moving eddy of liquid gold at the centre of the cup, and finally settle on top, in a thin, oily film of pasty foam. It reminded me of a steaming cup of Yak butter tea that is a must on holidays in the hills. When I finally took the first sip of my unremarkable keto coffee, “second thoughts” set in.

A few days earlier, in my dietitian’s cabin, I had listened intently while she explained the workings of a ketogenic diet, and squealed in delight when she announced that cheese, cream and butter were my new best friends. Once home, I treated myself to a dollop of malai (cream), freshly skimmed that morning. “Just what the doctor (my nutritionist, in this case) ordered,” I beamed.

However, it wasn’t long before the effects of decades-long conditioning, the incessant warnings and the ominous chants “Fat is evil, fat is bad”, kicked in. I constantly worried about all the fat I was consuming. It took me quite some time to reconcile with the fact that fats, after all, are not bad. They are, in fact, good.

Despite the bad press, fats continue to be indispensable to our kitchen and cuisines. A prolific cooking medium, fats impart texture to a dish, enhance or introduce flavours, and absorb nutrients. A source of essential fatty acids and other fat-soluble nutrients, fats are crucial to a healthy, balanced diet. Most importantly, fats—be it bacon grease, cheese or fresh cream from the fridge—are irresistible. However, when it comes to fats, discretion is important and moderation key.

One of the most enduring debates around fats revolves around the best cooking medium and healthiest option. In India, the frenzy around fat and its effects on health had demonized ghee—one of the country’s most popular cooking mediums since time immemorial—in haste. Traditional oils such as coconut and mustard came to be looked at with suspicion too.

But once again conscious and curious chefs and culinary enthusiasts have started revisiting traditional cooking mediums—ghee, butter, animal fats or oils extracted from plant sources—and discovering their virtues afresh. And the truth perhaps is that there is no one oil which is fit for everyone.

“The trick is to choose the right cooking oil and use it correctly,” says chef Sabyasachi Gorai. Different oils react differently to heat. Oils with a low smoking point, for instance, are unsuitable for deep frying, over-smoking destroys their flavour and nutrients. “Understanding the nature of the fat or oil is crucial in making best use of it,” he adds.

Choosing culturally and geographically appropriate fats suitable to the gastronomy of a region is also important. “In India, traditionally the cooking oil of choice has varied from one region to another,” says Thomas Zacharias, executive chef, The Bombay Canteen. While the pungent mustard oil is a kitchen essential in Bengal, Kashmir and Punjab, where mustard grows in abundance, groundnut oil rules kitchens in Gujarat, the highest producer of groundnut in the country, and coconut oil is preferred in coastal Kerala.

Ancient Indian texts like Arthashastra list numerous other oilseeds and oil, including safflower, castor and mahua in use around the country. Adivasi communities still use mahua oil to cook. Sesame oil—a south Indian pantry staple—has, in fact, enjoyed an elevated status, both ritualistic and culinary, since the Vedic ages. Down south, sesame or gingelly oil (even coconut and groundnut oil) would traditionally be cold-pressed in a chekku—a mortar-and-pestle like device used to crush seeds in order to extract oil without generating heat. This helped preserve the nutrients and properties of the oil, making cold-pressed oils far more beneficial for health. Traditional chekkus (known as ghani in the north) are in fact making a comeback and the demand for cold-pressed oils is on the rise too.

“There’s a reason why ghee and other such traditional cooking mediums have been around for ages. They are steeped in benefits,” says Sharad Dewan, executive chef, The Park Kolkata. Buddhist texts refer to bhesajja or five medicinal foods that include fresh butter, oil extracted from sesame, mustard or castor seeds, honey, molasses and ghee.

The healing properties of ghee can hardly be exaggerated. There are innumerable references to ghee in ancient texts. Some attribute special curative virtues to ghee made of thickened milk while others refer to the mahaghrta, ghee preserved for over a century, known for its miraculous properties. Interestingly, Lokapakara, written in medieval Karnataka, mentions synthetic butter made by mixing oil, curd, buttermilk and ghee in equal quantities and butter made of thickened milk infused with medicinal roots, turned into yogurt and churned.

Dewan, who is passionate about ancient culinary knowledge, stresses on seasonality with regard to cooking fats. “Lighter oils are best suited for summers, while heavier oil and ghee are better during the winters,” he says. Ancient Ayurveda too emphasizes seasonal dietary practices and offers specific stipulations on fat. Charaka, in his ancient treatise on Ayurveda, recommends using ghee in autumn, oil (sesame oil in particular) during the rainy season and animal fats during spring.

Animal fats might not be used as prolifically in Indian cuisines as in some cuisines of the West, but there are quite a few interesting instances of cooking with it. The Vinaya texts in fact refer to edible fats from animals like pig, fish, alligator, bear and ass. The Buddha allowed monks consumption of these fats during illnesses, thereby underscoring the fortifying properties of animal fats.

One fantastic source of nutrients and flavour is fish oil or fat. It could carry a whole dish on its shoulders. In Bengali kitchens fish fat and entrails are ingeniously used to make fritters jazzed up with finely chopped onions and fiery green chilies, or a curry made with sliced onions, green chilies. Some recipes call for thinly sliced potatoes or cubed brinjal, or a splotch of mustard paste. Pig or goat fat make for delicious fritters too.

Or take the nihari for instance. The slow-cooked meat stew infused with the fatty goodness of bone marrow is a lesson in the tongue-tingling virtues of animal fat. “Fat is essential to some of our kebabs too. While making seekh kebabs, we add extra lamb fat or even chicken fat to the mince to make the kebabs moister,” says Dewan.

However, in some parts of the North-East, animal fat is one of the principle mediums of cooking. “In Nagaland, for instance, little oil is used in cooking. The food is either boiled or cooked in pork (animal) fat,” says Zacharias, recalling his recent trip to the state. For the hunting tribes of Nagaland, animal fat is more readily available. Besides, the Nagas in general waste no part of the animal. “The fat is extracted, cooled down to room temperature, and once coagulated, the fat is hung up in the kitchen,” adds Zacharias.

Lard and dripping is sometimes used in Goan cooking too. Consultant chef Gracian D’Souza talks about a family recipe for feijoada, a pork and bean stew of Portuguese origin, which uses lard. On certain days De Souza makes make a traditional vindaloo with preserved presunto (dry-cured ham from Portugal) fat or replaces the butter in a traditional chicken liver pâté with Goan chouriço fats. “The fat is a game-changer,” he says.

Dewan, on the other hand, has a soft spot for ghee. “It is one of the best cooking mediums,” he says. Inspired by flavoured oils, chef Dewan nowadays stocks up on flavoured ghee that he makes in-house. There’s chilli-infused ghee, ghee steeped in flavours of whole spices, garlic ghee and ghee flavoured with panch phoran (Bengali five-spice mix). “I use it as a topping, temper dals with it or even use it for basting fish or meat,” says Dewan. Another way to use flavoured ghee is to pour it on top of piping hot steamed rice,” Dewan adds.

Gorai too often makes ghee in-house. “Besides, I source ghee from different parts of the country, each one distinct in flavour. My ragi mudde, for example, come topped with ghee from Mysuru,” says Gorai, an advocate of local ingredients.

Mustard oil is yet another favourite among modern chefs today. Zacharias finishes his rendition of the Kashmiri harissa—winter delicacy of rice, meat and spices cooked unhurried through the night—with a splash of charcoal-smoked, spice-infused mustard oil. Gorai uses cold-pressed mustard oil for quite a few of his dressings, with excellent results.

ALMOND BUTTER

Loaded with healthy mono-

unsaturated fats, vitamin E and omega-3, almond butter is often dubbed as the most nutritious nut butter. Eat it straight out of the jar or as a dip to go with crudités. Or use it to make a batch of gooey brownies.

CASHEW BUTTER

Naturally sweet, cashew nut butter will help satiate your sugar cravings sans the evils of added sugar. Besides cashew nuts come loaded with antioxidants. So cashew butter is rich both in flavour and nutrition.

PISTACHIO BUTTER

Relatively low-cal pistachio butter is a good source of antioxidants and protein. Spread it on toast, add it to a smoothie or even whip up a dressing.

COCONUT BUTTER

This is not the same as coconut oil—it’s a buttery paste made with desiccated coconut pulsed at high speed for several minutes. Tiny shreds of coconut remain in the butter. Spread it on bread or use it for baking.

WALNUT BUTTER

Walnut butter is loaded with antioxidants, essential omega-3 fatty acids and healthy polyunsaturated fats. Pair it with a bowl of raw vegetable sticks for the perfect afternoon snack.

First Published: Sun, Nov 04 2018. 10 29 AM IST